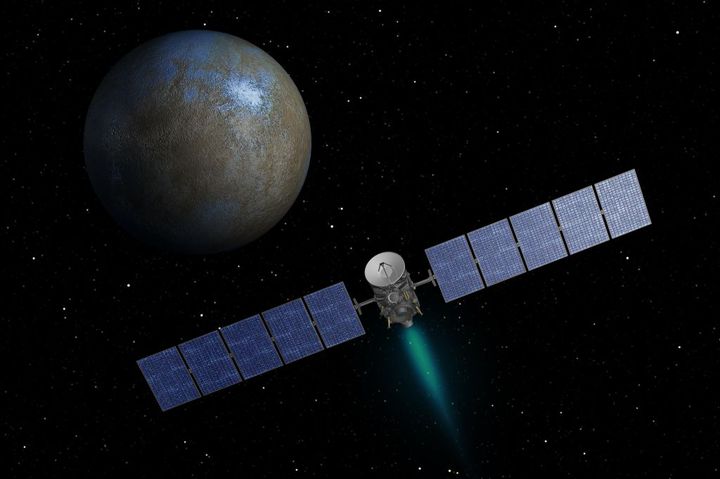

A spacecraft is set to make history tomorrow. NASA's Dawn spacecraft is preparing to be the only machine ever to spend an extended period at two worlds in the solar system. Dawn is on approach right now to a dwarf planet called Ceres, and tomorrow -- if all goes to plan -- it will be inserted into orbit to spend at least several months orbiting Ceres.

What's neat about Dawn is not only its extended exploration of Ceres and asteroid Vesta, but also the kind of engine it has on board. In part, Dawn uses a technology called ion propulsion. An ion is a molecule that has a charge because it has extra electrons. The technology has been tested before in space, notably on NASA's Deep Space 1 mission. But can it be useful here on Earth?

First, let's talk a bit about how the engine works. NASA says Dawn's mission requires it: "The demanding mission profile would be impossible without the ion engines -- even a mission only to asteroid Vesta (and not on to Ceres) would require a much larger spacecraft and a dramatically larger launch vehicle," NASA wrote.

Dawn actually has three engines to make sure it has enough fuel available for its entire mission. But the spacecraft only uses one thruster at a time. What the thrusters do, NASA said, is speed up ions using electrical charges. The ions are from xenon fuel and the technology only uses a little bit of power and fuel at a time. The tradeoff is it takes a long time to go anywhere. The thrust builds up in airless space, but it takes longer to accelerate the spacecraft than with conventional engines.

So think about it; in space there is no air, and ion propulsion appears to be suited to that situation as long as you are patient. It wouldn't be a good technology to push humans through the solar system, because the longer you spend on the journey the more chance there is of something going wrong! However, if you can imagine a colony of people on Mars receiving regular shipments from Earth, an ion propulsion engine on a cargo spacecraft could be useful as long as they are timed appropriately.

Here's the surprise, however. A 2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology-led study says that ionic thrusters on aircraft -- that's right, conventional aircraft that fly on Earth -- could be more efficient than jet engines. So what gives?

The study assumes an engine design where current goes between two electrodes, which creates a phenomenon called "ionic wind." It was first found in the 1960s, but the study showed it produces more power than previously believed: 110 newtons of thrust per kilowatt. A typical jet engine only produces two newtons per kilowatt. The ions would push the jet along by pushing air molecules.

But there are problems. The density of the propulsion is very thin, which would require the thrusters to be placed on just about the entire plane. There also are immense voltae requirements. If we could figure out these issues, however, imagine the applications. It would be a true "silent running" with jets quietly slipping through the atmosphere. They also would produce no heat, making them ideal for stealth-type aircraft.

You can read more about the study in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. It was led by MIT's Kento Masuyama.

Top image: NASA/JPL-Caltech