Complaints that large legacy companies can't innovate abound. Some folks go as far as to say that corporate innovation “is broken.”

This is, perhaps, an exaggeration. Large companies are still quite good at what is commonly known as incremental innovation, which is an improvement of already existing products or services; they’re also doing a decent job in streamlining operations and cutting costs.

However, it’s definitely true that many corporations are much less successful in transformational innovation, which is the creation of new products and businesses. Consider this: of 11,000 consumer product launches in North America in 2008-2010, only six had first-year sales of more than $25 million, maintained at least 90% percent of sales volume the next year, and produced cumulative two-year sales that exceeded $200 million. Only six, which is 0.05%.

The major reason for this lack of transformational innovation abilities seems to be obvious: a hallmark of any successful modern corporation is flawless, impeccable execution. Unfortunately, while perfecting execution and establishing the culture of predictability and control, corporations lose the culture of entrepreneurship, the habit of experimenting and taking risky bets. That’s why transformational innovation, with its high rates of uncertainty and failure, struggles to take root in the corporate soil.

The question, therefore, is how large legacy companies can start innovating big again?

Can Large Companies Innovate Like Startups?

Ten years ago, the business world was taken by storm by a concept called “Lean Startup.” Proposed by entrepreneur Eric Ries, the Lean Startup methodology postulated that every startup was in fact an experiment attempting to answer a question. But the question was not "Can this product be built?" but, instead, "Should this product be built?"

Central to the lean startup methodology was the assumption that by addressing the needs of early customers and building their products and services iteratively, startups could dramatically reduce market risks and sidestep the need for large amounts of initial funding (hence “lean” startup).

So popular the Lean Startup methodology has become that calls started soon for large companies to adopt it, too. Indeed, a number of legacy companies (General Electric, Qualcomm, and Intuit) have responded to these calls by implementing the lean startup methodology.

Unfortunately, the very hallmarks of the Lean Startup methodology - rapid experimentation, iterative testing-learning cycles, and rapid failure - don’t come naturally to many large companies. They excel at executing known business models, not creating them. And “rapid failure” is still an anathema to many corporations, despite loud calls to “celebrate” them.

Of note: Durathon, a production unit of the GE’s Energy Storage division, opened with a great phanfare in 2011, quietly closed in 2015. Durathon’s main product, sodium-ion batteries, created by using the Lean Startup methodology, has failed to achieve its market size targets.

Of course, some specific Lean Startup techniques - rapid experimentation being, perhaps, the most notable - can and should be adopted by large organizations. But to expect that many of them will be capable of innovating like startups is plain unrealistics.

It’s All About Ecosystems

Many academics and business practitioners correctly point out that the Lean Startup methodology was created in large part to help startups overcome a paucity of assets. But paucity of assets is not a problem for big companies. On the contrary, they have plenty of available resources, and not using them for innovation defies the very purpose of being a large company. So instead of trying to imitate startups, the thinking goes, large companies should instead work with them.

A notable proponent of this idea, Michael Docherty, suggests (in his book “Collective Disruption”) that corporations should support transformational innovation by creating innovation ecosystems including startups. In this innovation symbiosis of sorts, startups will provide large companies with disruptive ideas along with a playground for testing and early prototyping, whereas large organizations will use their resources to scale up the most viable ideas.

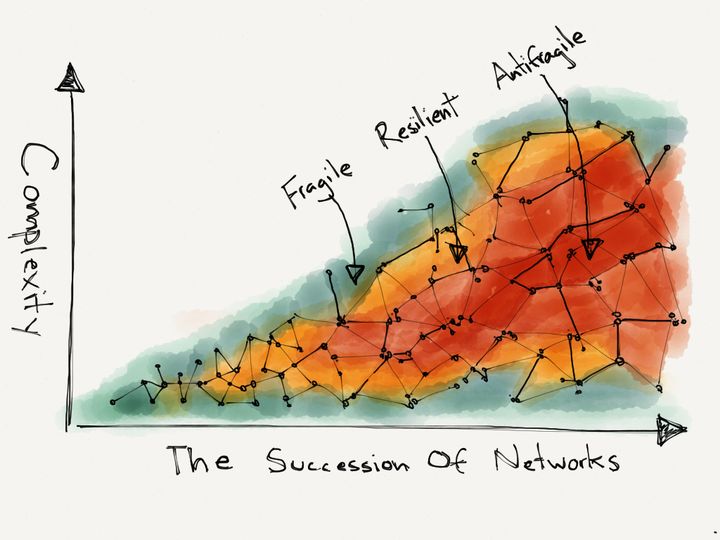

Granted, creating innovation ecosystems or even simply participating in them, doesn’t come naturally to many large corporations, either. And yet, innovation ecosystems are gradually becoming popular both in academic literature and among business practitioners.

It is important to note that the very concept of the innovation ecosystems idea is changing. The current thinking is that innovation ecosystems should include not only large companies and startups, but other interconnected actors, including governments, civil society, small- and medium-size companies, and universities. Recently, it has become apparent that innovation ecosystems may include even competing enterprises. A special term “coopetition” has been coined to describe innovation involving competitors. I wrote about “coopetition” in a recent HeroX post.

Much will have to be learned to make innovation ecosystems a viable approach for large companies to innovate. But a consensus is emerging that this type of corporate innovation will become mainstream.

The Best of Both Worlds: Being “Ambidextrous”

And yet, the idea that large companies can and should engage in transformational innovation, in addition to incremental, is far from dead. In 2004, Charles O’Reilly and Michael Tushman wrote an influential paper for the Harvard Business Review titled “The Ambidextrous Organization.” O’Reilly and Tushman argued that corporations don’t have to choose between investing in existing (core) and creating new businesses; they can do both (be “ambidextrous”) by establishing corporate structures supporting both incremental and transformational innovation.

In order to achieve that, companies should learn how to simultaneously “exploit,” i.e., fully utilize its existing capabilities and portfolios (incremental, cost-cutting, and efficiency focused innovation), and “explore,” i.e., engage in defining goals and targets outside of the scope of their current products, services, and business models (transformational innovation).

Appreciating the difficulty of the “exploration” part of the ambidexterity, O’Reilly and Tushman argue that while pretty much every company understands the importance of the ideation part of the innovation process, they routinely fall short in their ability to incubate and scale these ideas. While startups, too, can do a great job in generating novel ideas and incubating them, it is the scaling part of the innovation process - the part that utilizes the company’s sizable assets - that distinguishes the ambidextrous organization from a startup. Putting this simply, ambidextrous organizations can generate and incubate ideas as efficiently as startups, but they can also use their size to successfully scale them up into viable new businesses.

A list of organizations achieving the ambidexterity status of is still quite short, but it is growing. A recent publication mentioned a data analytics company LexisNexis; UNIQA, a subsidiary of Austria's largest insurance company; and the retail giant Walmart as three successful examples of truly ambidextrous organizations.

Being part of an innovation ecosystem and being ambidextrous share a few fundamental features. Both models require openness to external sources of innovation; both require flexibility in relationships with outside partners; and both require the creation of some corporate structures to facilitate the innovation process. It is therefore up to any particular large company to choose the model that best fits its strategy, objectives, and corporate culture. Or, perhaps, a new, “hybrid,” model can be invented combining the best features of the two original concepts.

The one thing is clear in any case: large size should not stop large legacy companies from aspiring to innovate like nimble startups.