Remember the days of the video store? It was no trivial matter to find the latest movie release at that time. You'd stroll down to the neighbourhood video store, which had VHS (Video Home System, or large videotapes) and DVDs. If you were lucky, there would be some of that release available for you to borrow or buy. If not, you'd have to come back at another time to pick it up.

We're pretty lucky these days that a lot of this material is available online, with one of the major providers being Netflix. The service is now so popular that you can find it in dozens of countries, with releases tailored to your tastes and needs. All you need to do is look at the homescreen to get a better sense of the content that you might find interesting.

This technology has not come easily. Netflix relies not only on user inputs, but also computer algorithms to help it figure out what to do next. Some of this work can be attributed to the Netflix Prize, which ran between 2006 and 2009. The aim was to figure out how much somebody would enjoy a movie, based on what they had already watched.

"Netflix is all about connecting people to the movies they love," the company wrote on its webpage about the prize. "To help customers find those movies, we’ve developed our world-class movie recommendation system: CinematchSM. Its job is to predict whether someone will enjoy a movie based on how much they liked or disliked other movies. We use those predictions to make personal movie recommendations based on each customer’s unique tastes. And while Cinematch is doing pretty well, it can always be made better."

The company asked that competitors try to beat Cinematch's predictions by 10%. The stipulation was the company would have to share how they would do it with Netflix and anyone else who asked -- in other words, they would be making the algorithms accessible to all and not proprietary.

To entice people to participate, Netflix offered a $1 million grand prize as well as a $50,000 progress prize to the top competitor for each year that the contest ran (which ended up between 2006 and 2009).

Netflix allowed that it was quite possible that somebody would come up with a better formula, and added that there was no need to pay money to participate -- or even to use Netflix at all.

"Now there are a lot of interesting alternative approaches to how Cinematch works that we haven’t tried," Netflix said. "Some are described in the literature, some aren’t. We’re curious whether any of these can beat Cinematch by making better predictions. Because, frankly, if there is a much better approach it could make a big difference to our customers and our business."

The contest opened on Oct. 2, 2006, and some reports indicate that Cinematch's results were already beaten in the first week. While it's hard to verify the accuracy of those reports, what is known is that by the end of the first year there were several teams that qualified for the Progress Prize. The mood was optimistic that the prize would be won at some time soon.

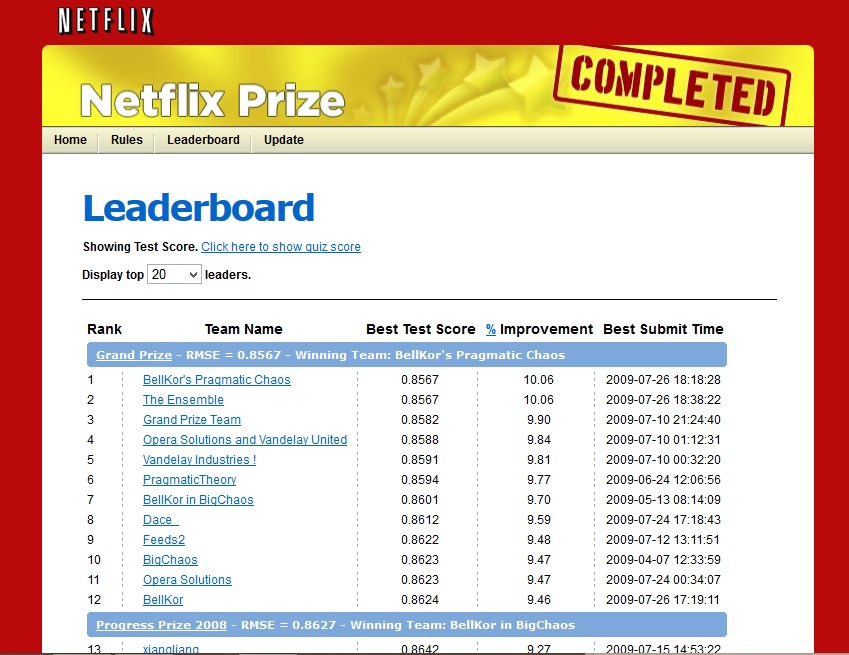

A screenshot of the Netflix Prize top competitors. Credit: Netflix

It actually took three years, but by the end there were two competitors that were practically tied in the rankings: BellKor's Pragmatic Chaos and The Ensemble. In the end, Netflix elected to award the Grand Prize to BellKor's because they submitted their results earlier, even though Ensemble's accuracy was slightly better. You can read details of BellKor's submission here.

Netflix planned a second iteration of the contest in 2010, but cancelled it due to Federal Trade Commission concerns over Netflix user privacy. What's more, the company never actually used much of the algorithm to improve its predictions. That's because the algorithm was better designed for the DVDs Netflix used to rent at the time. Today, Netflix is more about streaming -- which requires a different type of prediction.

Top image: Netflix has brought us a long way from the days of DVDs. Credit: Netflix / Wikimedia Commons